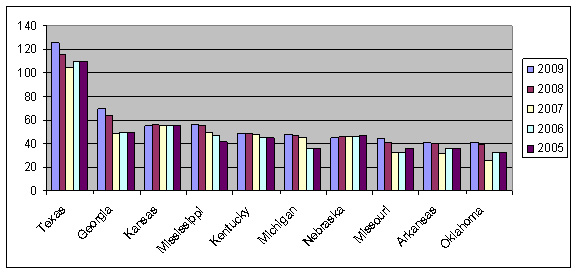

The chart below shows the ten states with the highest number of distressed or underserved counties in 2009, along with the data from 2008 through 2005 for those same states. To clarify, the FFIEC list identifies specific community tracts and the counties in which those tracts are located. The data below represents the number of counties in each state that have one or more distressed or underserved community tracts.

As the chart indicates, several of these states show relatively small changes over the five-year time period. Texas, Georgia, Mississippi, Missouri, Arkansas and Oklahoma show an increased number of counties in 2008 and 2009 compared to prior years. The data from Nebraska, Kentucky and Kansas, however, have remained almost flat.

Obviously, we don’t have the data here to understand why these particular states routinely have distressed or underserved community tracts in more counties than other states. But, since the composition of these “top ten” hasn’t changed much in five years, it’s probably safe to say the banking community hasn’t found an effective and sustainable means of serving many of these communities.

The 2009 data reports that in Texas alone, there are 335 distressed or underserved tracts, spread out among 126 counties. Among those tracts, poverty is the most pervasive problem; 173 tracts are designated as impoverished, while 120 have suffered from population loss. Another 85 tracts are in remote rural locations. Only five of the tracts have a noted unemployment problem. (Some tracts fall into more than one of these categories).

In 2005, Texas had 258 distressed or underserved tracts among 109 counties; 125 of the tracts were designated as impoverished, 120 had experienced population loss, and 85 were in remote locations. Twenty-six tracts had problems with unemployment. The change from 2005 to 2009 in Texas’ data looks to be largely driven by an increase in the number of poverty-stricken communities.

Residents of poor, shrinking and/or remote communities aren’t the ideal “target” for most banks. But the conventional school of thought supports the notion that these customers do offer opportunity for banks. They can be weaned onto starter banking services and eventually converted into more sophisticated banking customers.

A bank acquisition team that addresses these customer segments early in the strategic planning process can devote the resources necessary to gain a foothold in underserved areas. That foothold can then develop into a strong competitive advantage, as residents and businesses benefit from the financial support of a community-oriented bank.

For additional reading on addressed underserved communities, see:

• Dryades Savings Bank Case Study http://www.cdars.com/_docs/case-study-dryades.pdf

• FDIC Advisory Committee on Economic Inclusion http://www.fdic.gov/about/comein/agendaFeb52009.html

• Reaching Underserved Borrower Prospects: A Case Of A Small Rural Bank http://www.cluteinstitute-onlinejournals.com/PDFs/200632.pdf